William K. Vanderbilt II – known to family and friends as Willie K. – loved the oceans and the natural world. In his seagoing global travels, he collected fish and other marine life, birds, invertebrates and cultural artifacts for the personal museum he planned to build on his Long Island estate.

William K. Vanderbilt II – known to family and friends as Willie K. – loved the oceans and the natural world. In his seagoing global travels, he collected fish and other marine life, birds, invertebrates and cultural artifacts for the personal museum he planned to build on his Long Island estate.

William Vanderbilt exhibited thousands of the marine specimens he had gathered – one of the world’s most extensive, privately assembled collections from the pre-atomic era – in his own marine museum, the Hall of Fishes, which he opened to the public in 1922. Wings of the mansion house galleries of his natural-history and cultural-artifact collections. The Habitat with its nine wild-animal and marine-life dioramas was created by artisans from the American Museum of Natural History.

Today, the 43-acre waterfront Vanderbilt Estate, Museum and Planetarium complex counts among its extensive collections (which total more than 40,000 objects) the mansion, curator’s cottage, a seaplane hangar and boathouse, antique household furnishings, rare decorative and fine art, the archives and photographic record of Mr. Vanderbilt’s circumnavigations of the globe, and published books of his travels.

William Vanderbilt realized the potential for his sprawling estate to become a museum “for the use, education and enjoyment of the general public.” He established a trust fund to finance the operation of the museum and deeded it to Suffolk County, New York, upon his death in 1944. The county opened the museum to the public in 1950.

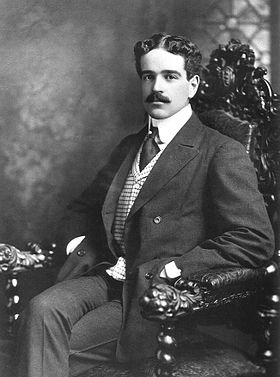

William Kissam Vanderbilt [1878-1944] spent many of his earliest days sailing around the world on his father’s various yachts. Young William was educated by tutors, attended St. Mark’s Preparatory School, and studied at Harvard.

William Kissam Vanderbilt [1878-1944] spent many of his earliest days sailing around the world on his father’s various yachts. Young William was educated by tutors, attended St. Mark’s Preparatory School, and studied at Harvard.

When he was twenty years old, he met Virginia Graham Fair, known as Birdie. She was several years older and had been born in poverty. But by the time she met young Vanderbilt she was a wealthy young woman. Her father, James Fair, nicknamed “Slippery Jim,” was one of the four “Silver Kings” of the rich Comstock Lode in Virginia City, Nevada.

On March 26, 1899, William and Virginia were married in a Roman Catholic ceremony in the conservatory of the bride’s sister in New York City. Her only jewelry, except for the diamond clasps on her veil, was the pear-shaped pearl surrounded by rubies worn as a pendant, the gift of the groom. The couple intended to spend their honeymoon at Idle Hour at Oakdale but the house burned to the ground on their wedding night and they were forced to go elsewhere. They leased the Villa Belvoir at Newport that summer. Then, it was back to work in his father’s office in Grand Central Station, at least for a while.

William was an accomplished sailor and yachtsman. In 1900, he won the Lipton Cup trophy with his 70-foot yacht Virginia and was presented the award by Sir Thomas Lipton, who created the races. In 1904, William sponsored the first Vanderbilt Cup Race [for motor cars], on Long Island. Later he and a group of investors formed the Long Island Motor Parkway Corporation and built one of the country’s first modern paved parkways.

He served in the Navy during World War I, and was a lieutenant commander in the U.S. Naval Reserve.

After ten years of marriage and the birth of three children, the Vanderbilts separated. Birdie, however, did not file for divorce until April 1927. William was then at home in Passy, France, Birdie at a hotel in Paris. No alimony was requested, as Birdie had inherited many millions from her father and brother. And, John D. Rockefeller Jr. had recently bought her ornate Gothic residence on Fifth Avenue in New York City for $1,500,000.

In September, following the divorce, William and Rosamond Lancaster Warburton, of Philadelphia, were married in a civil ceremony at the mayor’s office in Paris. Rosamond was born in 1897 in Worcester, Massachusetts. In 1919, she was married to Barclay Harding Warburton Jr., son of Major Warburton and his wife, Mary Brown Wanamaker, daughter of the department store founder John Wanamaker, of Philadelphia. She divorced the year before her marriage to William.

William owned a hunting lodge and preserve in Canada, a farm in Tennessee, a place at Fisher’s Island in Florida (complete with seaplane hangar, docking facilities, an eleven-hole golf course with each hole named after one of his yachts, tennis courts, and swimming pool), and the summer estate at Centerport, Eagle’s Nest. William died in early 1944 of a heart ailment; Rosamond died three years later. The estate, along with a $2,000,000 fund for its perpetuation, was left to Suffolk County, Long Island.

The design of the Eagle’s Nest mansion was unusual for estate architecture on Long Island. Seldom seen in the region, its palatial Spanish Revival style is actually less “Spanish” than a personal evocation of Vanderbilt’s Mediterranean impressions as interpreted by his architects. The estate was built in stages between 1910 and 1936. Its features include a classic pantile roof, stucco facades, and a central courtyard. The elegant ironwork was created by Samuel Yellin, the foremost iron artisan of his day.

Two extensive buiding periods followed the original construction of the house, and transformed it into the extensive mansion complex that visitors see today. Each expansion was prompted by incidents in Mr. Vanderbilt’s life. The first was his inheritance of $21 million after his father’s death in 1921 and subsequent marriage to Rosamond Warburton in 1927. The second was the tragic death of his son William III in 1933. A visit to the Eagle’s Nest mansion, preserved as it was when the family lived there, offers visitors a glimpse into the life of William K. Vanderbilt II.

The mansion began in 1910 as a modest bachelor’s retreat, built at a comfortable distance from the legendary concentration of Gold Coast estates located closer to New York City. The original bungalow was perched high above Northport Bay. On the waterfront below, a boathouse and wharf accommodated Mr. Vanderbilt’s greatest passion, sailing. His other passion, motor car racing, is represented on the estate by the two-story automobile garage (now the museum’s Education Center) and by a large revolving turntable located on the lower level of the Memorial Wing, where Vanderbilt’s custom-built 1928 Lincoln touring car is displayed.

Whitney Warren (1864-1943) was a cousin of the Vanderbilts. After deciding to study architecture in 1883, he enrolled at Columbia University but stayed for only one year. In 1884, he left for Paris to attend the Ècole des Beaux Arts and remained for ten years, studying under Daumet and Girault. Warren returned to New York in 1894 and, with characteristic resourcefulness, convinced one of his first clients, a lawyer named Charles Wetmore (1867-1941), to become his partner. The new firm’s bid for recognition came in 1899 when the New York Yacht Club (an organization familiar to William K. Vanderbilt, II) held a competition for a new clubhouse. Warren & Wetmore received the commission, which established their reputation in New York.

Almost immediately, the firm was engaged as architects for the New York Central, Michigan Central, and Erie and Canadian Northern Railroads. They were responsible for the design of the entire Grand Central Terminal Group, which began with the design of the Grand Central Station (1903-1913) and ended with the New York Central Office Building [1928]. The complex included several Vanderbilt-financed hotels, among them the Vanderbilt (1911), the Biltmore (1912), and Hotel Commodore (1919).

Considering these associations with the Vanderbilt family, it is reasonable to attribute the 1910 design of “Eagle’s Nest” to Warren & Wetmore, although documentary evidence has yet to be found that confirms this attribution. Stylistically, the original buildings on the estate did resemble some of the early work the firm produced on Long Island, such as the outbuildings for Clarence MacKay’s “Harbor Hill” in Roslyn (1904). In addition, although no records have been located for the first phase of the mansion’s construction, later blueprints and drawings confirm that the firm was commissioned in various capacities from 1926 until 1930. During this period, Warren & Wetmore also designed the Spanish-style Deepdale Golf and Country Club in Great Neck (1926) for William K. Vanderbilt II.

Little is known about Ronald H. Pearce. His name first appears in the archives of the museum in correspondence that dates from 1922 between the architectural firm of Warren & Wetmore and William K. Vanderbilt II. The letter details the construction of the walls along Little Neck Road. In 1923, Vanderbilt wrote to Pearce in care of Warren & Wetmore concerning the pool and other matters. Other correspondence dealing with numerous contractors such as interior decorative painters and changes to the power plant document his involvement with improvements at “Eagle’s Nest” until 1930.

Published sources about Pearce are equally elusive. The first that appears in connection with the Vanderbilts is an article by Pearce for the Architectural Record (December 1926), which describes the newly completed Deepdale Golf and Country Club in Great Neck (Warren & Wetmore, Architects). The article is meticulously complete with regard to the building, but offers little editorial comment about the architecture or the architects. In 1928, a New York Times article refers to a piece by Pearce that had appeared in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects about the reconstruction of the Library of the University of Louvain in Belgium. Also dating from 1928 is a Town and Country article entitled “A Rambling Spanish House on Long Island” in which the author states that William K. Vanderbilt II had “sent Mr. Ronald Pearce to Spain to study the architecture of the different parts of the country.” The article reported that “the result of this profitable journey is a coordination of the different architectural expressions found in the North and the South of Spain into the attractive, rambling composition which is “Eagle’s Nest” on Northport Harbor.” The article thus implies that the altered and enlarged summer estate, which was transformed from a “four-room English cottage, useful for week-end visiting” into a Spanish-inspired mansion and complex of numerous other buildings, was quite possibly the work of Ronald H. Pearce.

From the museum’s archive of architectural drawings, Pearce’s name appears for the first time on an architectural drawing proposing an addition to the Hall of Fishes. A Town and Country article in 1937 credits Pearce with the original design for this building (1922), although the earlier drawings have not survived. In all probability, Pearce had begun working on the “Eagle’s Nest” project in the early 1920s and continued as Warren & Wetmore’s architect for the estate after the retirement of Warren from architectural practice in 1931. His drawings for the Memorial Wing and other alterations to “Eagle’s Nest” indicate that he was a competent Beaux Arts architect with dramatic flair. Most importantly, he was skilled at designing additions and alterations that harmonized with previously built sections of the estate.

Ronald Hoyt Pearce maintained an office in New York City at 11 East 44th Street between 1932 and 1940.

Richard Morris Hunt, Architect

Richard Morris Hunt, Architect

John Butler Snook, Architect

John Butler Snook, Architect

John Butler Snook, Architect

Peabody & Stearns, Architect

www.salve.edu

George B. Post, Architect

Richard Morris Hunt, Architect

Peabody & Stearns, Architects

Richard Morris Hunt, Architect

www.newportmansions.org

Richard Morris Hunt, Architect

www.biltmoreestate.com

Robert H. Robertson, Architect

www.shelburnefarms.org

Peabody & Stearns, Architects

(remodeled by Horace Trumbauer, Architect, for James B. Duke)

www.newportrestoration.com

Richard Morris Hunt, Architect

www.newportmansions.org

McKim, Mead & White, Architects

McKim, Mead & White, Architects

http://www.nps.gov/vama/

McKim, Mead & White, Architects

http://view.fdu.edu/?id=196

Richard Howland Hunt, Architect

Warren & Wetmore, Architects

www.lihistory.com

Horace Trumbauer and Carrere & Hastings, Architects

McKim, Mead & White, Architects

Summer residence “Eagle’s Nest,” Centerport, Long Island, NY

William Kissam Vanderbilt, II (1878-1944)

Warren & Wetmore, Architects

Ronald H. Pearce, Architect

John Russell Pope, Architect

www.fisherislandclub.com/History

Addison Mizner, Architect

Treanor & Fatio, Architects